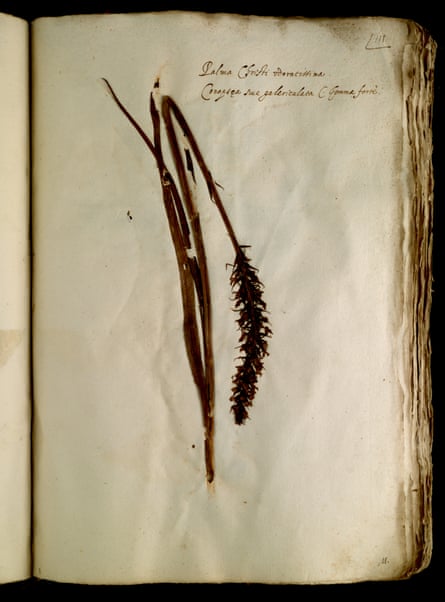

A collection of pressed flowers collected from the hills of Bologna 500 years ago provides insight into how the climate crisis and human migration are changing the landscapes of northern Italy.

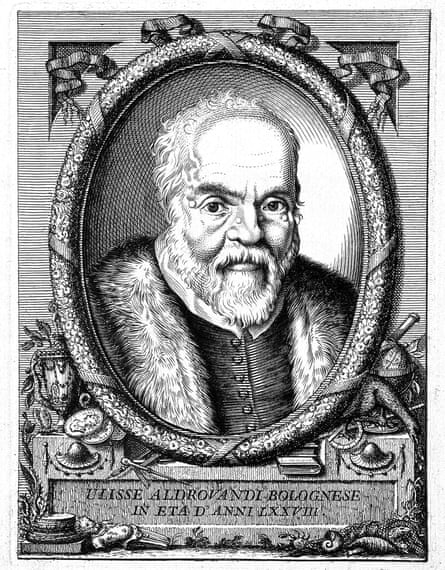

Collected between 1551 and 1586 by Renaissance naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi, the 5,000 delicately cut and dried plants form one of the richest collections of its time.

Aldrovandi’s initial goal was to identify plant species and understand which ones could be used for pharmaceutical purposes. Nearly half a millennium later, its carefully pressed specimens are helping botanists document the enormous changes in the surrounding landscapes, according to new research published by the Royal Society.

In Aldrovandi’s time, the hills of Bologna were rich in species that are now threatened or even extinct, such as motherwort, used for medicinal purposes and now probably extinct in the region. The total number of species has increased since the 1500s, but the quality of the flora has declined, with many rarer species declining, the researchers said. The Italian population increased by 560% during the period studied.

The Aldrovandi herbarium is made up of 15 books, each containing up to 580 specimens glued to sheets. The collection includes notes on the frequency, abundance, ecology, local names and uses of species in traditional medicine. Researchers believe this is the oldest example of a herbarium containing such detailed notes. “From a historical and scientific point of view,” write the researchers, “the importance of this herbarium is inestimable.”

“The Aldrovandi herbarium preserves the memory of the first signs of a radical transformation of European flora and habitats,” says the newspaper.

Part of this transformation is the massive influx of non-native species. At the time the collection was assembled, only 4% of the flowers were American species, almost exclusively grown in private or botanical gardens. Plants such as peppers and zucchini were imported through early exploration in Central and South America. Since then, non-native flowers from the Americas have increased by 1,000%, illustrating the growing importance of American-European trade routes beginning in the Renaissance.

“We would never expect to see such a big difference,” said lead researcher Dr Fabrizio Buldrini of the University of Bologna. “These increases are frightening, in some ways, because they are a clear sign of profound human impact. »

Buldrini’s team compared the flora collected by Aldrovandi with the collections made by Girolamo Cocconi (1883) and records compiled in the Emilia-Romagna region between 1965 and 2021. They examined the area of the plains surrounding the Po River and its tributaries, where they were able to make comparisons between data sets.

The data also shows the effects of the “Little Ice Age,” which extended into the mid-19th century. High mountain species such as silver geranium are usually found above 1,700 meters above sea level, but Cocconi found it at 800 meters above sea level. The mountain buttercup is now only found above 1,000 meters, but during the “Little Ice Age” it was found at 300 meters.

Aldrovandi also helped establish the city’s botanical garden, one of the first in Europe. A number of important collections were established in his time and in the following centuries, with Bologna becoming a “kind of cradle of modern botany and herbaria”.

Since the 1970s, a project has been launched to map the entire flora of the region, resulting in a database containing over 500,000 records.

Overall, the discovery highlights the importance of the dried flower records, the researchers said. “A recent scientific trend is to reject these collections as dusty, cumbersome and useless – very expensive to store and maintain and virtually useless for modern research. There is nothing wrong anymore: herbaria are indispensable and irreplaceable data banks for many areas of research,” said Buldrini.

Worldwide collections contain 390 million specimens, according to the Index Herbariorum. Buldrini added: “To reject them would be to reject our historical archives, our monuments or our art collections. »

This article was amended on November 8, 2023 to add text clarifying that Emilia-Romagna is a region of Italy and to correct a link to the source study.

Find more Age of Extinction coverage here and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston And Patrick Greenfield on X (formerly known as Twitter) for all the latest news and features