WWhen I was young, I was fascinated by the mysterious characters that appeared on the covers of vinyl albums. Where did Roxy Music find its endless supply of glamorous women? Who was the weather-beaten fisherman in the front of Cure’s Standing on a beach and how did he know the cure? Like many children, I thought that the nine celebrities on the cover of Group on the run by Paul McCartney and Wings – including Michael Parkinson, comedian Kenny Lynch and Liberal MP Clement Freud – represented the real Wings line-up, which would have made for a difficult studio environment.

In the age of Google, these questions can be answered in seconds. Roxy Music knew a lot of the models and Bryan Ferry dated half of them. The (retired) fisherman’s name was John Button. (“The man on the album cover was not a member of the Cure,” Wikipedia notes.) Parkinson did not perform with Wings. Some mysteries, however, proved more difficult to solve.

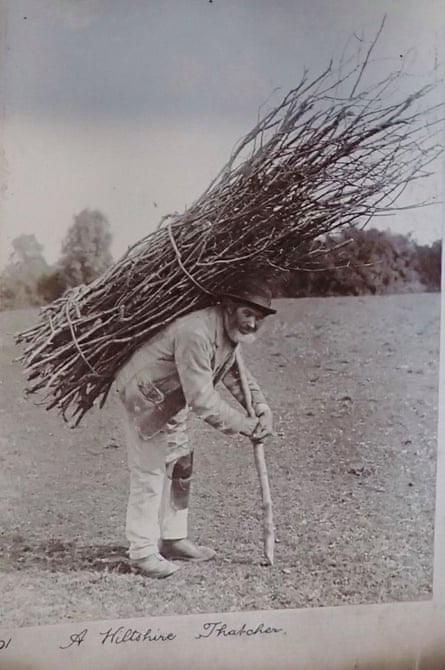

Led Zeppelin’s untitled fourth album has always held a special fascination. Better known as Led Zeppelin IV, he was also nicknamed “Zoso”, after the occult runes on the cover. The old man in the center, bent double by his load of tied branches, looks like a sinister apparition from an MR James ghost story.

Historian Brian Edwards, who came across the original photograph while researching another subject, apparently identified the man as Lot Long, a Victorian thatcher from Wiltshire, and the photographer as Ernest Farmer. Individual fans can decide whether this discovery enriches the work or spoils the enigma.

When physical music sales collapsed 20 years ago, it was widely predicted that the album and its cover art were doomed and that music would henceforth be consumed as just a string of file names. This hasn’t happened for a variety of reasons, from vinyl’s surprising tenacity to the growing importance of merchandise in an artist’s bottom line. The Spotify app may not offer the same visual spectacle as a 12-inch cover, but it still demands images that can make a visual impact in the form of tiny digital squares. Faces, whether those of the artist or someone else, are ideal.

Some artists are lucky enough to know the right faces. The bleary-eyed cigarette smoker on the Arctic Monkeys’ debut album is Chris McClure, a Sheffield acquaintance of the band, while the doe-eyed kid on the U2 albums Boy And War is Peter Rowan, the younger brother of Bono’s friend Guggi.

Others seek to establish an aesthetic kinship with the distant or the dead. Morrissey’s eye for evocative 1960s imagery played an invaluable role in positioning the Smiths in a community of stars that existed in a romantic dream space beyond 1980s reality – an invitation to join no only to songs but to a vision of the world. Alain Delon and Billie Whitelaw said yes; Albert Finney and George Best refused.

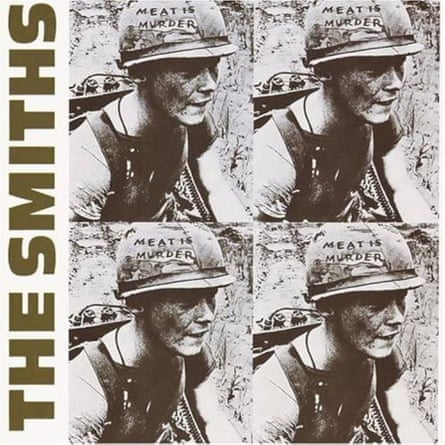

Often, legal permission is only required from the photographer or rights holder, not the subject, which can cause discomfort. To play a role in music history without your knowledge is to experience a strange kind of celebrity in which your face becomes synonymous with someone else’s vision. US Marine Michael Wynn, pictured in Vietnam in 1967, belatedly protested in 2019 saying he “wasn’t really happy” that the slogan on his helmet was changed from “Make War Not Love” to the title The Smiths’ 1985 album: “Meat Is Murder.”

Some U.S. states have “right of publicity” laws, which allow appropriation of an individual’s image without their consent to civil liability. Former model Ann Kirsten Kennis sued Vampire Weekend and her label for $2 million after the band used a 1983 Polaroid of her on the cover of their 2010 album. Contra, claiming that the photographer who authorized it did not in fact take the photo. “I felt like someone was exploiting me,” she said. Vanity Fair. “Who do these people think they are that they can just take my picture from God knows where and post it everywhere?” (The lawsuit was settled for an undisclosed amount.)

Grunge band Tad came across a striking photo of a half-naked hippie couple in a thrift store photo album and used it in 1991. 8-way Santa, only to discover that the woman was now a fiercely unimpressed born-again Christian.

after newsletter promotion

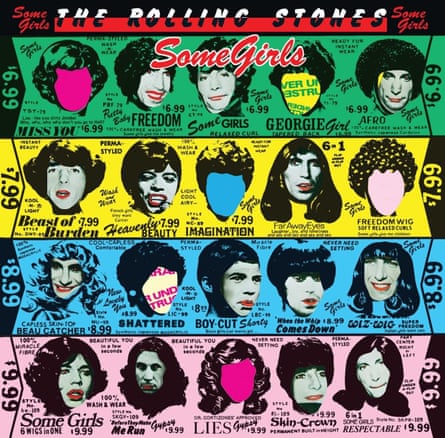

Portraits of celebrities, whose faces are valuable assets, benefit from additional legal protections. The Beatles asked permission from every living person featured in the collage on Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Group but the Rolling Stones’ more cavalier approach to image rights in 1978 Certain girls managed to outrage Lucille Ball, Raquel Welch and Judy Garland’s daughter, Liza Minnelli. A modified sleeve was produced.

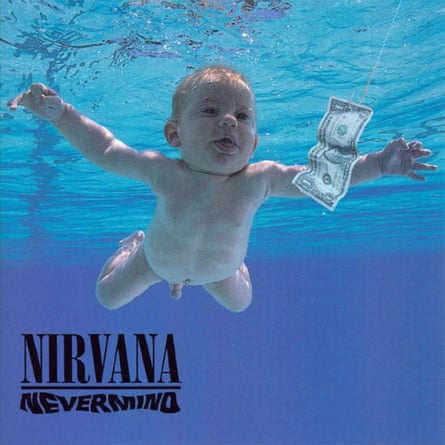

Young cover stars, meanwhile, may develop retrospective reservations that cast an ethical veil over famous images. David Fox, the 12-year-old who makes a funny face on Placebo’s debut album, later claimed that the image sparked such intense bullying that he had to leave his school. Spencer Elden, who appears as a naked baby on the cover of Nirvana Nevermind, recently prosecuted for alleged sexual exploitation of children. The suit was dismissed twice; Elden appeals. U2’s “boy” Peter Rowan has no legal claims, but he called out U2 for their pro-choice stance during the 2018 Irish referendum on abortion rights, which was embarrassing.

Artists tend to have a double-edged view of copyright: they value protection of their own work but crave the freedom to capture the perfect image, like a musical sample, without having to obtain absolute permission or permission. to take into account the feelings of the individuals concerned.

In this regard, Led Zeppelin’s mystical obsession with England’s past served them well. Lot Long died in 1893, so whether he would have enjoyed his association with Stairway to Heaven, cryptic runes and rock’n’roll bacchanals, we will never know.